These program notes were written by Elise Groves for a performance of Bach’s St. John Passion. This concert was presented by The Bach Project in conjunction with Ashmont Hill Chamber Music on March 5, 2023.

Every epic story has a main antagonist – a “big bad” – to provide the conflict and give the hero a reason for their actions. Whether it is Thanos in the Marvel Universe, the Empire and Darth Vader in Star Wars, or the countless villains in Disney movies, everyone knows and can identify the main enemy in most major stories about good and evil. But who is the enemy in the St. John Passion? Who is truly responsible for the death of Jesus?

Before going any further it should be clearly stated: it is NOT the Jews. The backdrop of this story is the tension between the Jewish people and the Roman occupation. Jesus was Jewish, as were his disciples (including Judas). It would be equally as inappropriate to eliminate all references to Judaism as it would be to focus on that as the single issue of the St. John Passion. Unfortunately there is a long tradition of the Christian church using “the Jews killed Jesus” as an excuse for unspeakable atrocities – committing them and allowing others to do so – and it is both wrong (the Romans executed him) and unacceptable in Christian theology which includes the precept to treat others as one would wish to be treated and to take care of everyone, no matter their religious practice or any other distinguishing characteristics.

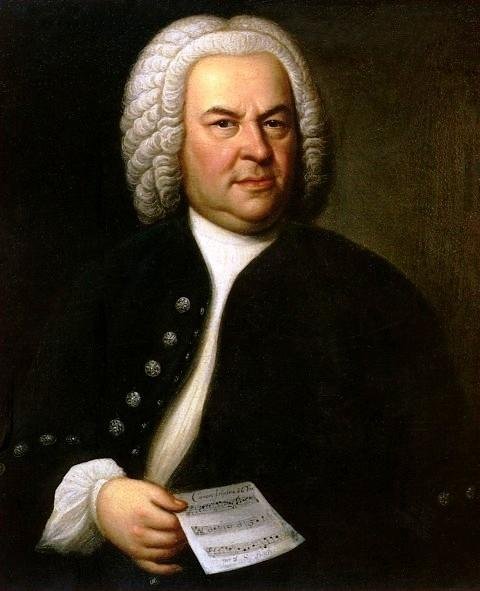

Antisemitism was rife in the Christian (and Lutheran) church in the 1700s, as it has been at many points in history. Martin Luther was clear about his antisemitism, and his bias most definitely impacted his translation of the gospel of John into German. The portions of the text taken directly from the gospel of John (the recitatives of the Evangelist and the conversations between Pilate, the mob, and Jesus) are pulled from Luther’s translation of the Bible, which pointedly highlights the role the Jewish leaders took in handing Jesus over to the Romans. The portions added to the libretto (the chorales, arias, and a few of the major choruses) provide more commentary on the story and expand on the general theology of the Lutheran church at the time without any such references. While Bach’s personal views on the Jews are somewhat unclear, he was a devout Lutheran so it is reasonable to assume he shared the attitudes of his day; his statements about the Turks and the Pope from Cantata 18 leave little doubt about his opinions there, and this is likely no different. The historical Lutheran view of the Jews is clear in the libretto and it should cause discomfort, especially reflecting on the tragic outcomes of that attitude throughout history. To present the St. John Passion as it is, without any discussion of these issues, would be wildly irresponsible and there is no need to cause further harm. At the same time, to erase all references to Jesus’ ethnicity would remove all context from an historical event and eliminate the opportunity to confront difficult chapters of history and learn from them. These translations seek to find a middle ground by adjusting a few key words, indicated by brackets. (online note: if you are interested in these, please reach out via my contact page!)

Much has been written about fascinating other aspects of the St. John Passion – the different revisions Bach made over his lifetime, the symbolism and numerology that can be found in the structure, and a much greater discussion of both Lutheran theology and antisemitism – and the reader is encouraged to seek out experts on those topics for a fuller understanding. For the sake of simplicity, the remainder of these notes will cover the story as it is told in the libretto and the relevant elements of Christian practice, as opposed to debating the validity of religious belief. The story of Bach’s St. John Passion is really an exploration of the question of who is truly responsible for the death of Jesus, and other issues are better left for theologians, historians, and personal convictions.

In looking for the enemy in the St. John Passion, several possibilities arise. Judas betrayed Jesus, but in the libretto, as in the gospel of John, he disappears after the first few minutes (this is one of many differences between the writings of John and Matthew). The Jewish leaders were following their laws for someone who was clearly developing a following and potentially could upset the precarious truce they had with Rome. The Roman soldiers were more or less “just following orders”, which leads back to Pilate.

Pontius Pilate is mentioned by name as having caused the suffering of Jesus in most of the creeds used by the Christian Church. He certainly sat in judgement of Jesus, as he would have for any person questioning imperial authority in that region. Pilate was appointed the prefect of Judaea by Roman Emperor Tiberius. He was not particularly well-liked by either the Jewish people or the Samaritans (especially after his paganism and cruelty resulted in riots among both groups). He also had to maintain Roman authority over the Jewish people, and the situation with Jesus put him in a no-win scenario. The claim that Jesus was the “King of the Jews” was a direct challenge to Pilate and to Rome. But Bach tips his hand and hints that Pilate isn’t the sole enemy with the line “from then on Pilate sought a way that he might release him”, as well as Pilate’s three separate statements of “I find no guilt on him” (a mirror image of Peter’s three denials). Pilate chose to hide behind “the desires of the people” and literally washed his hands of the situation. Certainly not a choice to be proud of, but not one that qualifies him to be the main antagonist. In fact, a close look at the dialogue between Jesus, Pilate, and the mob reveals that Jesus himself is the one who keeps moving the story forward, at times providing answers and at times withholding them – Jesus is the one essentially in control of the outcome.

This is where the role of the passion story in Christianity becomes important. Bach’s St. John Passion was premiered on April 7th (Good Friday), 1724 at the St. Nicholas Church in Leipzig. It was originally designed to be performed in two halves with a sermon in the middle, and the chorales were specifically chosen from hymns that were frequently in use that the congregation would know and recognize. The message of the passion in Christianity, massively oversimplified, is that Jesus took the punishment for the sins of everyone and in doing so conquered sin and death, leading to the resurrection celebrated on Easter. It is the “everyone” that becomes relevant here, and this was the role Bach provided for the chorus.

While soloists take on specific identities (Jesus, Pilate, servants, etc.), the chorus fills in the rest. The chorus could be the congregation of believers taking a step back and recognizing the spiritual significance of various events, as in the opening and closing choruses and the chorales. The chorus spends a significant amount of time functioning as the mob in conversation with Pilate, refusing to disperse or be appeased until they have satisfied their own lust for blood. To help illustrate this, most of the traditional labels of “aria, chorus, recitative” have been removed from these translations and replaced with the names of the characters from the story and the various roles the chorus is filling. It is in the many identities of the chorus that the message of the St. John Passion becomes clear – the blame is not on the individuals but rather on the group, which includes anyone and everyone. Bach’s performance would have included soloists who also sang choruses, as this one does, which further makes the point that everyone, from the main characters to the onlookers that would have joined the mob, is implicated in the outcome of the story.

Stepping out of the Christian paradigm, the idea of shared culpability is not one that most people embrace willingly. Modern culture encourages a view of “us vs. them” or “self vs. other” and provides a seemingly endless number of criteria for determining who is the “other”. At the same time, both the story of the St. John Passion and the history of antisemitism in the text and translations of the gospel of John make it clear that identifying someone as “other” has fatal consequences. Both history books and current events are full of the stories of people who have been determined to be “other” by a group with power. The passion illustrates our shared culpability for those circumstances; the answer to “who is the enemy?” is quite plainly, “we are”. At times we may have played any of the roles or inhabited any of the identities of the passion story – the message goes beyond any one belief system. The question that remains for all of us at the end of the piece is then, “What am I going to do about it?”